Over at The Panda’s Thumb we see a

post that highlights a study done on limb loss in vertebrates. John Lynch states,

An interesting article in this week's edition of Nature suggests that at least in some fish, alterations in a single gene bring about evolutionary change in the form of limb (fin) loss.

Two follow-up posts on TPT, each by P. Z. Myers, can be found

here and

here. In the first follow-up P. Z. states,

Some of the complicating features of developmental genetics are pleiotropy and multigenic effects: that is, that the genes required to build an organism are all tangled together in an intricate web, with multiple genes required to properly assemble each character (that's the multigenic part), and each gene having multiple effects on multiple characters (that's pleiotropy). One might think of the organism as a house of cards, each card supporting all of the cards above it, so that tinkering with any one piece leads to catastrophic collapse. This isn't the case, of course. While developing systems are all elaborately interlocked, they also exhibit modularity and surprisingly robust flexibility.

In the second follow-up P. Z. states, with regards to the idea that the modularity and robust flexibility of a system could be used as evidence of design:

Quite the contrary, I see evidence of mechanisms that permit integrated evolution of organisms, with no designer required.

He provides more detail, via his own blog Pharyngula with,

Development. Evolution. Genes. Fish. What's not to like?. In it we see the following image:

Essentially, what we're hearing is that the integrated complexity found within the genetic structure of these species achieved its integrated complexity through blind chance because... well... they're

here aren't they? Isn't it amazing how nature has solved the problem of spitting out either limbs or fins? - all with the flip of a switch!

Yet imagine the power of templates. Imagine the efficiency in using a plan that allows for minor alterations that garner major changes. Imagine a set of instructions, a code - if you will, that allows one to step through a financial accounting program and, depending on the desired outcome, run a report of actual cost expenditures by region vs. running a report of revenue by project. Shucks, I don't have to imagine it at all - I ran a set of those reports today on a piece of software designed by semi-intelligent people.

On the morphological side, consider the skeletal and muscular structure of the human arm and hand.

Now note a robotic arm and hand that mimics the same functional capabilities as its human counterpart. As the website for the Shadow Robot Company states,

"The human hand has twenty-four powered movements. Shadow have implemented every single one, with all the power and range of movement, that the human hand has... The muscles in the upper arm and torso are analogous to the human's."

Have the robotic designers used the basic structural and morphological elements of a human arm and hand as a

guide for their design criteria?

How about a steam rotary engine? Let’s look at the schematics for such a device.

If we cross reference now with electrical rotors we find the following from

Penntex: a

rotor, and a

stator.

Cross referencing with pump rotors we find, at

Seepex pumps: a

universal joint

Common sense tells us that there are similarities in these various human designs because they are all working off the same basic template (i.e., rotary motor design). Variances within the details are due to varying specific parameters with regards to design criteria as well as to function, materials, power supply, etc.

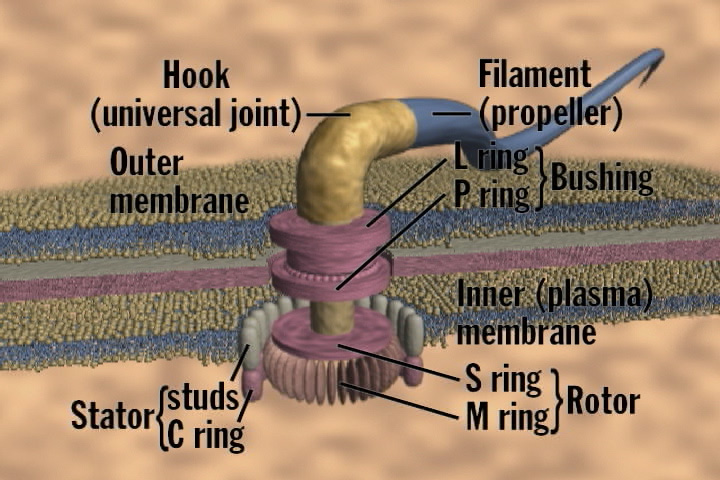

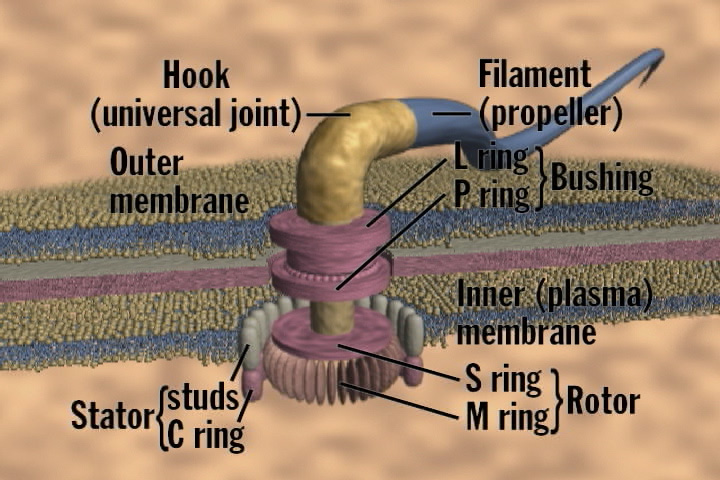

Now compare the human artifacts with a flagellar motor per the

NCBI and

ARN websites:

,

How interesting that the components of the flagellum precisely match up with the

designed components of rotary motors.

Additionally, note that the work in robotics, as well as the development of the rotary motors, did not occur through blind, random chance, but through intentional, rationalistic thought processes – i.e., through design.

Essentially, what we're hearing is that the integrated complexity found within the genetic structure of these species achieved its integrated complexity through blind chance because... well... they're here aren't they? Isn't it amazing how nature has solved the problem of spitting out either limbs or fins? - all with the flip of a switch!

Yet imagine the power of templates. Imagine the efficiency in using a plan that allows for minor alterations that garner major changes. Imagine a set of instructions, a code - if you will, that allows one to step through a financial accounting program and, depending on the desired outcome, run a report of actual cost expenditures by region vs. running a report of revenue by project. Shucks, I don't have to imagine it at all - I ran a set of those reports today on a piece of software designed by semi-intelligent people.

On the morphological side, consider the skeletal and muscular structure of the human arm and hand.

Essentially, what we're hearing is that the integrated complexity found within the genetic structure of these species achieved its integrated complexity through blind chance because... well... they're here aren't they? Isn't it amazing how nature has solved the problem of spitting out either limbs or fins? - all with the flip of a switch!

Yet imagine the power of templates. Imagine the efficiency in using a plan that allows for minor alterations that garner major changes. Imagine a set of instructions, a code - if you will, that allows one to step through a financial accounting program and, depending on the desired outcome, run a report of actual cost expenditures by region vs. running a report of revenue by project. Shucks, I don't have to imagine it at all - I ran a set of those reports today on a piece of software designed by semi-intelligent people.

On the morphological side, consider the skeletal and muscular structure of the human arm and hand.

Now note a robotic arm and hand that mimics the same functional capabilities as its human counterpart. As the website for the Shadow Robot Company states, "The human hand has twenty-four powered movements. Shadow have implemented every single one, with all the power and range of movement, that the human hand has... The muscles in the upper arm and torso are analogous to the human's."

Now note a robotic arm and hand that mimics the same functional capabilities as its human counterpart. As the website for the Shadow Robot Company states, "The human hand has twenty-four powered movements. Shadow have implemented every single one, with all the power and range of movement, that the human hand has... The muscles in the upper arm and torso are analogous to the human's."

Have the robotic designers used the basic structural and morphological elements of a human arm and hand as a guide for their design criteria?

How about a steam rotary engine? Let’s look at the schematics for such a device.

Have the robotic designers used the basic structural and morphological elements of a human arm and hand as a guide for their design criteria?

How about a steam rotary engine? Let’s look at the schematics for such a device.

If we cross reference now with electrical rotors we find the following from Penntex: a rotor, and a stator.

If we cross reference now with electrical rotors we find the following from Penntex: a rotor, and a stator.

Cross referencing with pump rotors we find, at Seepex pumps: a universal joint

Cross referencing with pump rotors we find, at Seepex pumps: a universal joint  Common sense tells us that there are similarities in these various human designs because they are all working off the same basic template (i.e., rotary motor design). Variances within the details are due to varying specific parameters with regards to design criteria as well as to function, materials, power supply, etc.

Now compare the human artifacts with a flagellar motor per the NCBI and ARN websites:

Common sense tells us that there are similarities in these various human designs because they are all working off the same basic template (i.e., rotary motor design). Variances within the details are due to varying specific parameters with regards to design criteria as well as to function, materials, power supply, etc.

Now compare the human artifacts with a flagellar motor per the NCBI and ARN websites:

,

,  How interesting that the components of the flagellum precisely match up with the designed components of rotary motors.

Additionally, note that the work in robotics, as well as the development of the rotary motors, did not occur through blind, random chance, but through intentional, rationalistic thought processes – i.e., through design.

How interesting that the components of the flagellum precisely match up with the designed components of rotary motors.

Additionally, note that the work in robotics, as well as the development of the rotary motors, did not occur through blind, random chance, but through intentional, rationalistic thought processes – i.e., through design.

No comments:

Post a Comment